Stock car racing in the United States closed the deal on its biggest ever race in 1993 when NASCAR CEO Bill France Jr. and Indianapolis Motor Speedway president Tony George announced that the Winston Cup Series would pay their inaugural visit to IMS on August 6, 1994.

The year 1993 featured a number of powerful moments for NASCAR: Ned Jarrett calling his son, Dale’s, first Daytona 500 victory; the tragic losses of 1992 title rivals Alan Kulwicki and Davey Allison; and, Rick Hendrick bankrolling a full-time campaign for a boyish rookie out of Indiana.

From the city of Vallejo, California, Jeff Gordon’s family migrated from the San Francisco Bay Area to Pittsboro, Indiana to support his budding motorsports career.

Gordon was a racing phenom, winning in disciplines ranging from BMX bikes, go-karts, and quarter midgets all before he was 10 years old. While that sounds relatively normal nowadays, this was highly irregular in America during the late-1970s.

Once his family made the move to Indiana, Gordon got behind the wheel of a sprint car at 14 years old and won three races, avoiding an insurance hurdle set by companies in CA.

The early success put Gordon on the fast track to open-wheel racing at the nearby Indianapolis Motor Speedway instead of racing in its shadow.

Earning a USAC license at 16 (the youngest ever at the time), the youngster impressed by winning several high-profile events in USAC and World of Outlaws, such as Eldora, Night before the 500 (twice), the Hut Hundred, the Belleville Midget Nationals, and the 4 Crown Nationals.

His successes brought higher honors, becoming the 1990 USAC national Midget champion and tacking on a USAC Silver Crown title the next year.

Due to the nature of CART (now known as the NTT IndyCar Series), Gordon needed a mountain of funding to make his way into the premier American open-wheel division, and while his age and performance were impressive, it didn’t move the needle enough to reach the IndyCar paddock.

So, Jeff and his stepfather John Bickford began experimenting with alternatives.

Three-time Formula 1 world champion Jackie Stewart noticed the young American’s talent and attempted to reach out to Jeff about traveling to Europe for a tryout in Formula Three, an offer that would’ve put the adolescent racer in the F1 pipeline.

Jeff inevitably balked on that offer and another to drive for Cal Wells’ Stadium Super Trucks team to drive a stock car at former two-time NASCAR champion Buck Baker’s driving school.

The transplant Hoosier took the three-day course at the high-banked Rockingham Speedway where another former Winston Cup champion took notice of the young driver’s raw talent.

Benny Parsons called up Hugh Connerty, a restaurant magnate and aspiring racer. Gordon tested Connerty’s Pontiac at Rockingham that week, setting the best times of the week and outpacing the restauranteur’s times.

Connerty offered Jeff a three-race deal toward the end of 1990 in the NASCAR Grand National Series (now known as Xfinity) where rain washed out qualifying. Jeff attempted to race his way into the event through what was called a hooligan’s race where Jeff’s instructor, Randy Baker, ruined his bid to start and his car.

Not to be deterred, the 19-year-old wunderkind put the #67 Outback Steakhouse car on outside pole for the race at Rockingham before bowing out of the race following an early accident.

Despite missing out on qualifying again in Martinsville, Gordon managed to find a full-time opportunity in the Grand National Series for 1991 with Ford and Bill Davis Racing.

Jeff piloted the #1 Ford Thunderbird for much of the season, showing flashes and winning Rookie of the Year after an 11th-place points finish, but 1992 would play host to his big break.

Reuniting with his crew chief from the Connerty days, Jeff Gordon and Ray Evernham sat on the pole for three of the first four races in 1992 in the newly-sponsored #1 Baby Ruth Ford.

The fourth of those races occurred in Atlanta where Winston Cup team owner Rick Hendrick spotted the little-known racer driving the wheels off of his car on the way to Gordon’s first NASCAR win.

Gordon’s roommate at the time, Andy Graves, worked for Hendrick Motorsports and told Jeff that his boss wanted to meet with him, something Gordon brushed off as a joke.

Labeling himself a packaged deal with Evernham, Gordon and Bickford walked away from offers from Ford team owners Jack Roush and Junior Johnson to stay with the blue ovals before agreeing in principle with Hendrick to drive a third Chevy Lumina in 1993.

Gordon’s decision infuriated many at Ford, making the rest of his season more tumultuous than it should have been. He excelled through the vitriol, however. Gordon swept the Charlotte races during the season and notched a 4th-place result in points.

DuPont signed to sponsor Gordon at HMS on a four-year deal, solidifying the youngster as a Winston Cup mainstay for the foreseeable future. After an attempt to acquire the #46, Hendrick settled on the number 24 for Gordon’s car, the number he would debut with at the 1992 Cup season finale in Atlanta.

Gordon’s inexperienced crew left a roll of tape on his car during a pit stop early in the race. When Gordon’s vibrant rainbow Chevy merged onto the track surface, the tape punctured a hole in the nose of title contender Davey Allison’s grill, significantly altering Allison’s day.

Much like Allison, Gordon’s day was eventually undone by a crash when the #24 Lumina was swept up into an accident before retiring after 164 laps, the halfway point of the race.

Jeff’s maiden voyage set sail into the ruthless waters of NASCAR Winston Cup competition as a determined but inexperienced 20-year-old, but he made his presence felt early, leading the final 29 laps of the first Twin 125 race on his way to his first unofficial victory at NASCAR’s highest level.

The DuPont duo of Gordon and Evernham backed it up with a top-5 in the Daytona 500, the first of four top-10s in the first eight races. Gordon’s first chance at glory came in his first Coca-Cola 600 where the #24 car steadily climbed its way to second place, coming up one spot short to Dale Earnhardt.

Three races later in Michigan, the driver nicknamed “Wonder Boy” followed in his teammate Ricky Rudd’s tire tracks on his way to another runner-up finish, starting a streak of three straight top-10s that was leveled off by three straight finishes outside the top-30 in the following races at Pocono, Talladega, and Watkins Glen.

With 10 races left, Gordon sat an admirable 10th place in points, but seven finishes of 20th or worse sunk the rookie down to 14th in the final standings for 1993, still good enough to earn Rookie of the Year honors.

A year highlighted by 7 top-5s and 11 top-10s ended with optimism, despite 11 DNFs in a 30-race schedule.

Jeff and Ray entered their sophomore Winston Cup season with a full head of steam.

The Rainbow Warriors put together a solid piece for Daytona, coming home with another top-5 in the Great American Race. This was derailed the following week when Gordon was run over by Wally Dallenbach going into turn 1 with less than 25 laps to go.

After two respectable top-10s at Richmond and Atlanta, the DuPont race team went on a skid of six straight races where a 15th-place result in North Wilkesboro stood out as the lone bright spot in a dim period.

Having the misfortune of not finding victory lane yet in an official capacity, Gordon lined up the following week for the All-Star Open, a preliminary race for winless drivers to battle it out to join the grid with the previous year’s winners.

So, what did Jeff do? He led for 21 laps and found victory lane (unofficially) yet again. He went on to finish 14th out of 20 cars in the All-Star Race, but this was merely a tune-up for the next week: The Coca-Cola 600.

Charlotte evolved to become the capital of NASCAR with most of the teams being headquartered in the surrounding areas, including Hendrick Motorsports.

The 1.5-mile quad oval put drivers and teams to the test, often running over four hours in duration behind the wheel of the metal, mobile sauna for 400 laps over 600 miles.

Charlotte was the site of Gordon’s first pole position in the fall of 1993, and their lightning-fast Lumina made the series bear witness to a sequel, claiming his second career pole for the series’ longest day.

Jeff took the point for the first circuit before getting passed by All-Star winner Geoff Bodine. Gordon kept the #24 car in the mix all evening, staying within arm’s length of Rusty Wallace, Ernie Irvan, and Bodine.

As the cards began to fall, the final green-flag run of the race stretched out to 77 laps, meaning all of the leaders needed to return to the pits for one last stop.

Wallace abdicated the top spot for a pit stop on lap 375. Bodine pitted four laps later, leaving Jeff as the last one to get service of the lead group.

Knowing that time was of the essence, Evernham dialed up a risky strategy when he called Jeff into the pits on lap 382, sending his hotshot driver on track with enough fuel to get to the finish and two fresh right-side tires.

Ray figured that the time saved from fueling less and pitting for less tires would be just enough separation from Rusty to scamper away to a victory, and he was right on the money.

Jeff rounded turn 4 on lap 400 and crossed the finish line, earning his first career Winston Cup victory in his 42nd career start in the series. He defeated Wallace by four seconds, something he’d get accustomed to doing.

The 21-year-old worked and raced his whole life to make it to this moment. In a race full of grizzled veterans and savvy champions, the Wonder Boy outran them all in one of the most demanding events on the calendar.

He rolled into victory lane where the cameras caught him crying in his seat, the culmination of all those BMX and quarter midget races he won to put him into a stock car at this very track just three years prior.

Winning can ease internal tensions within a team and get them pointed back in the right direction. Coming into the 600, the DuPont boys sat an underwhelming 18th in points; whispers of a sophomore slump were starting to grow louder.

Over the next month, Jeff finished no worse than 12th with three top-10s, putting him back into the top-10 in season points. The next three races saw the 24 crew sweat, bowing out at Loudon and Talladega to put Daytona 500 winner Sterling Marlin within striking distance of bumping Jeff out of the top-10 yet again.

Enter: Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

The inaugural Brickyard 400 put Gordon back in familiar territory, a hometown race of sorts for the Indiana transplant. Making the weekend more special was the race taking place during Jeff’s birthday weekend.

The newly-minted 22-year-old racer had to alter his birthday plans to accommodate for Cup qualifying where his brilliant multi-colored car earned a third-place starting spot for the biggest race in NASCAR’s history.

Gordon took the lead for the first time on lap 3 when he advanced by pole sitter Rick Mast and held onto the lead through the race’s first two cautions before Geoff Bodine snuck by on lap 25.

The Rainbow Warriors kept the car near the top of the scoring pylon, Jeff biding his time before streaking past Harry Gant on lap 48 to retake the top spot. The #24 Chevy Lumina paced the field for 57 of the first 80 laps.

Wonder Boy would duck out of the lead periodically, all the while looming in the leader’s rearview mirror.

When the Fords of Geoff Brabham and Jimmy Hensley collided on lap 130, the field retreated to the pits for the money stop.

Having a mistake-free stop could be the difference between finishing 15th and etching your name into history as a winner at Indianapolis, the first winner of your discipline.

Evernham’s Rainbow Warriors serviced the #24 car and put their sophomore star back on track in the top-5. Now, it was up to the hometown kid to close out the race.

Cars rushed back to the green flag on lap 135 for a final 26-lap stint to the checkered flag. Wallace jumped out to an early lead that would be short-lived as Gordon rocketed by the next lap, setting up a duel between two California natives: Jeff Gordon and Ernie Irvan.

Ernie made his own pilgrimage to Charlotte about a decade before Jeff did. Growing up in Salinas on the south side of the Bay — opposite of Gordon to the north in Vallejo — Irvan opted for the stock car route as a teen, finding success in Stockton and Madera.

At the age of 23, Ernie left home on his own and headed east for the Carolinas, picking up odd jobs in and around the racing scene to make a living and connections. He moonlighted as a late model driver at night.

The California boy’s determination and raw ability caught the eye of team owner DK Ulrich in the late-80s who gave him his first full-time opportunity in Cup.

Complications with sponsor Kroger pushed Irvan to seek a more secure ride; he landed in the #4 Oldsmobile operated by Morgan-McClure Motorsports in March 1990.

Ernie scored his first victory in the Bristol night race later that year and took another prestigious win in the Great American Race the next season. He visited victory lane a handful of times with the team, but inconsistency plagued their championship viability.

When Davey Allison passed away in July 1993, Robert Yates approached him to replace Allison in the #28 car. Irvan wanted to accept; he was under contract, though.

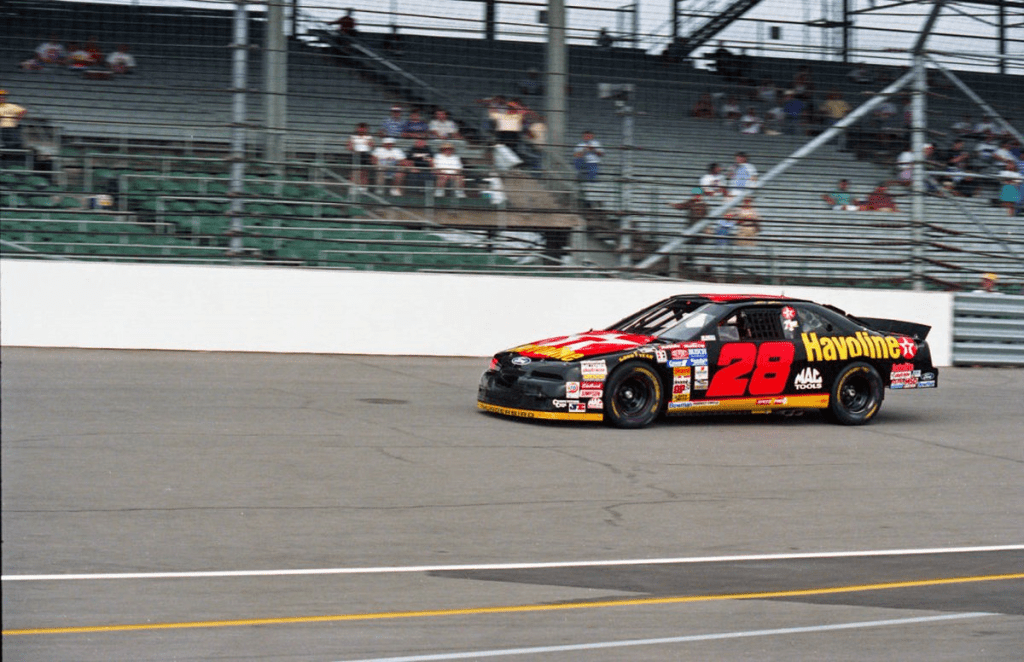

Eventually, cooler heads prevailed in the court of law, and after the race where Irvan put himself and MMM on the map three years earlier, the team gave him the boot when they left Bristol with Ernie assuming the reigns of the #28 Havoline Ford Thunderbird for the rest of 1993 and beyond.

Irvan won two races to close out 1993 and dominated the points the following season, notching 3 wins, 11 top-5s, and 14 top-10s in the 18 races leading up to Indianapolis.

The driver who became known as Swervin’ Irvan held the points lead coming into Indy and looked to be in good shape, going toe-to-toe with his California compatriot for much of the race.

In a sport dominated by East Coast good ol’ boys, these two West Coast guys wrangled their heavy, clumsy stock cars around the Brickyard like Jim Rathmann and Rick Mears did before them in IndyCars.

If you zoom out, this is the furthest thing from a NASCAR race in concept, yet it was one of the most badass battles in the sport’s long, storied history.

Irvan’s black Ford swiped the lead from Gordon’s for a few circuits until Gordon snuck back by in a matter of turns, the age-old game of cat and mouse.

Irvan’s car surged to the front again on lap 150 and began stretching his lead inch-by-inch, Gordon’s childhood dream fading out his windshield in the form of a faint Havoline logo on Ernie’s bumper.

Perhaps Jeff was biding his time for one more attack in the closing stages, but the cruel arms of fate intervened.

Irvan rapidly dropped pace on lap 155. Heading back into turn 1, his car wouldn’t wrap the apron like it had been, drifting to the outside and opening up a window for the opportunistic Wonder Boy.

The captain of the Rainbow Warriors blew back by Irvan with five laps to go for the final time as Ernie had a tire lose air and go flat, dropping him out of contention and out of the points lead.

Gordon was determined to not let anyone back by his technicolor torpedo, holding serve over the rebounding Brett Bodine for the final turns. Jeff exited turn 4, and ESPN announcer Bob Jenkins said:

…and Jeff Gordon is about to write his name in the racing history books. Years from today when 79 stock car races have been run here, we’ll remember the name — Jeff Gordon, winner of the inaugural Brickyard 400!

Beside Jenkins in the booth was the man responsible for Gordon getting his first break with Hugh Connerty four years prior, Benny Parsons. Parsons remarked that he thought he might cry during the cooldown lap.

Jeff pulled into the hallowed victory lane, the first car with fenders to grace since they were deemed too heavy and disruptive for open-wheel racing. Tony George approached Jeff and awarded him the first PPG trophy, in the shape of a brick.

The Wonder Boy turned his birthday wish into a reality, a win he could cherish forever.

With 12 races left, Gordon and Evernham proved they could win any week, anywhere, but not for the rest of 1994, only sniffing the top-5 at Richmond and Phoenix.

The DuPont duo struggled to close out 1994 just like their rookie year, concluding the season 8th in the final points with 2 wins, 7 top-5s, 14 top-10s, and unfortunately, 10 DNFs.

1994, that was just the beginning for Jeff Gordon, not just at Indianapolis but the NASCAR record book.

(Top Photo Credit: ESPN)